Inside Thailands first caviar farm

After six years of planning and problem solving, Alexey Tyutin donned sterilized gear and stepped into a chilly pond, plunging into the latest role of his varied career: fish milker.

As he gently massaged the slick belly of a sturgeon, the first tiny eggs began to pop out. Then it started to rain Thai gold.

As bowls filled with sturgeon eggs, he was elated, but vindication wasn’t on his mind. Everyone thought he was mad, but proving the numerous sceptics wrong wasn’t his aim. ‘I never felt this was impossible,’ he says of his feat, making caviar – a staple from his icy homeland in Siberia – in tropical Thailand.

The first harvest from Thai Sturgeon Farm in July was 22 kilograms. Tyutin expects to quadruple that yield this winter and aims to produce 1.5 tonnes a year. That won’t rival global caviar powers such as China, but certainly puts Thailand on the map.

And as well as expanding the boundaries of a booming global caviar-farming industry, Tyutin’s operation aims to be more sustainable. Thai Sturgeon Farm uses a closed-water system, minimizing pollution, and eschews chemicals and preservatives.

The milking process also means that the fish are kept alive, rather than being killed for their eggs – although many would still question what sort of life it is. Aquaculture will never be able to mimic life in the wild.

Nevertheless, Bill Marinelli, a long-time proponent of sustainable seafood in Thailand is a fan. The Covid crisis forced the closure of his Oyster Bar in Bangkok, but he’s an enthusiastic investor in Thai Sturgeon Farm. ‘Farms can kill 100,000 tonnes of sturgeon every year – just one farm. This is a great alternative.’

Caviar has been savoured around the globe for millennia. Its origins are hotly debated, but the Greek scholar Aristotle described the delicacy appearing at banquets in the fourth century BCE. The term comes from the Persian word khav-yar, meaning ‘cake of strength’. Persians harvested fish eggs on the Kura River, and Iranian caviar became among the most prized, and consequently most expensive, in the world.

The production of modern-day caviar largely takes place in China, where sturgeon have been a staple throughout history, although the native species are now so threatened that they’re all protected. The Chinese began by salting the roe of carp; technically, caviar applies widely to similarly prepared fish eggs. However, caviar generally refers to sturgeon eggs, one of the world’s most expensive foodstuffs.

Russia popularized and spread production and consumption, which was favoured by royalty and the wealthy across Europe and the Middle East. But Tyutin has memories of caviar being a staple during his childhood in Novosibirsk, in Siberia.

He describes being sent to the neighbourhood shop, where a giant mound of caviar glistened in a refrigerator. ‘I’d get a few scoops, spooned into a jar,’ says Tyutin, now aged 53. ‘Caviar was affordable for everyone.’

During the 1980s, he says, the former Soviet Union produced more than 1,000 tonnes – about three times the entire world caviar production nowadays. ‘Only 100 tonnes were exported,’ he says. The rest was consumed across the USSR. ‘Everyone had caviar.’

Then came the collapse of the Soviet Union and the lucrative Caspian Sea sturgeon fishery, which it shared with Iran, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. Beluga caviar, the world’s most prized variety, commanded prices of US$10,000 per kilo or more and became popular with chefs cooking in the world’s more ostentatious restaurants – until it was gone.

Overfishing and pollution prompted bans on sales of caviar from the Caspian Sea, where a huge clean-up campaign and restocking have been underway for more than a decade.

There are more than two dozen species of sturgeon, which are among the world’s oldest animals, descended from fish that date back to the early Jurassic period, about 200 million years ago. Some are already believed extinct.

In 2010, the International Union for Conservation of Nature placed 18 species on its Red List of Threatened Species, making sturgeon among the most endangered known group of species.

As stocks shrank, prices soared, fuelling the spread of farming operations. The largest have sprung up across China. The most famous are in an area southwest of Shanghai around Qiandao Lake, formed by a dam built under Chairman Mao during the 1950s. By far the biggest single producer is Kaluga Queen, which sells 80–100 tonnes annually – about a quarter of the global total.

Kaluga Queen reportedly supplies most of the top Michelin-starred restaurants in France and around the world. Many top caviar houses repackage eggs from China, often without mentioning the fact on the label. Yet, the stigma attached to Chinese caviar is largely a thing of the past, says Richard Ekkebus, director of culinary operations and food and beverage at the Mandarin Oriental Landmark Hotel in Hong Kong.

Ekkebus is a lifelong caviar fan. The Mandarin’s Michelin-starred sister restaurant, Amber, has a caviar menu, and Ekkebus serves a well-known dish of sea urchin in lobster gel, topped with a dome of 15 grams of hand-picked caviar. Amber uses more than a kilo a day. ‘China is the world’s largest caviar producer and they have really nailed it,’ he says.

Kaluga Queen also supplies sturgeon eggs to Caviar House, which in turn supplies most of Thailand’s top restaurants. But Tyutin isn’t concerned about competition as he introduces Thailand’s first locally produced caviar – Caviar House is also his company.

Tyutin became Thailand’s caviar king despite having practically no experience in the field beyond fetching jars of it in Novosibirsk as a boy. A resident of Thailand for 17 years, he first came as a tourist and was instantly smitten with the lush island of Koh Samui.

His background was in mechanical engineering, but he took after his grandfather, Alexey A Tyutin, a versatile engineer. ‘We called him Golden Hands,’ his grandson says. ‘He could fix anything.’ During the Second World War, his grandfather was chief engineer of the Novosibirsk Aviation Plant.

Koh Samui was still a sleepy island when Tyutin arrived in 2004, but a building boom of villas for visitors from Hong Kong and Singapore meant that it was stirring. Tyutin was soon building villas. Later, with Thai partner Noppadon Khamsai, he acquired land, put in roads and infrastructure, and constructed condominiums.

Then the global economic crisis in 2008 derailed their growing business. After disposing of the assets, Tyutin was considering what to do next.

He remembered an old friend in Moscow, Dr Vasily Krasnoborodko, who had devised an unusual, computer-controlled method of raising sturgeon. Fish lived in ponds and were fed and cared for automatically. A computer system monitored everything, from their growth to their readiness to produce eggs. Even the opportune time to milk the fish was determined by sonogram.

‘I asked him, “Could you build something like this here, in Thailand?”’ Tyutin recalls. Krasnoborodko had built farms in Russia, Latvia and Ukraine, all cold-weather areas. ‘He said he could build it anywhere. We just needed cold and water.’

The former is in short supply in Thailand, especially in Hua Hin, home of the Thai Sturgeon Farm. Hua Hin was once an obscure fishing village, 200 kilometres down the coast from Bangkok.

Then, in the early 1900s, Thailand’s king built a palace there, creating a royal retreat. A rail line followed, turning Hua Hin into Thailand’s first seaside resort. A sleepy getaway for the ensuing century, the town is now getting a makeover as the capital of Thailand’s caviar industry.

But, it’s hot. Temperatures in Novosibirsk drop to –20°C in winter and often as low as –30°C. During rare summer heatwaves, it may hit 30°C, which is still colder, by a couple of degrees, than the average temperature yearround in steamy Hua Hin. Tyutin solved the heating problem with a huge cooling system that operates across the 32-by 48-metre plant.

In 2016, the farm imported 3,000 fish fry from China. Tyutin chose a hybrid of the Amur sturgeon and the kaluga, the latter being prized in the caviar industry.

‘We’ve chosen this because it grows quickly and produces eggs the same size as beluga and kaluga, but faster,’ he says. As the fish grew and it became possible to determine their sex, males were separated and sold for food – a common practice as only females are required for the eggs.

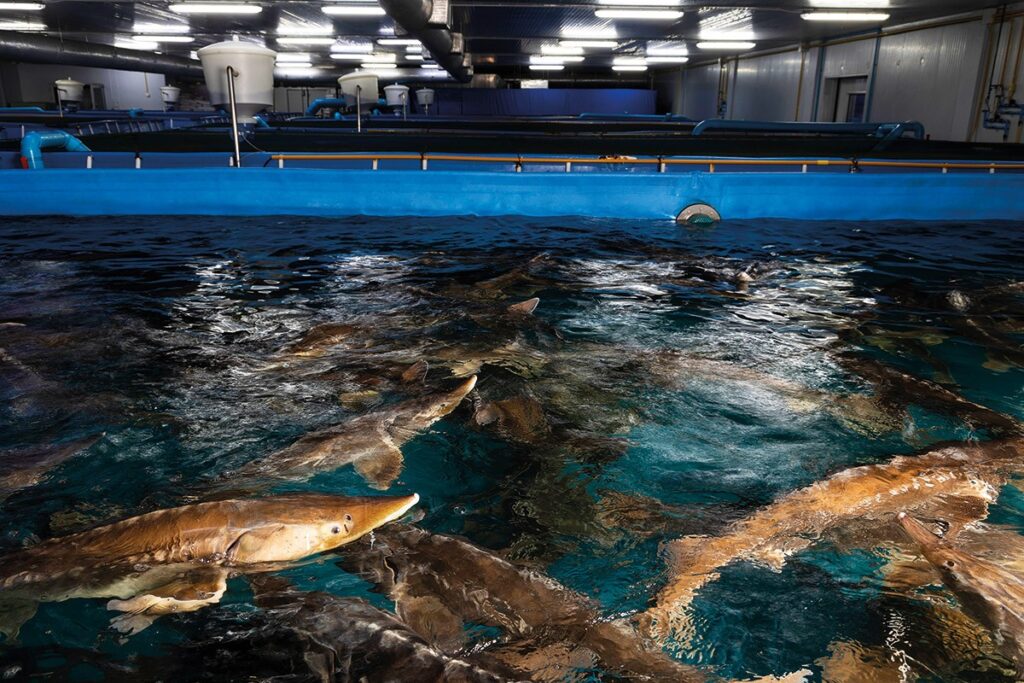

The farm now has about 1,800 female fish in ten tanks. They are kept in temperatures of around 22°C until egg production begins. Selected fish are then moved to a separate pond where the temperature is gradually lowered to wintering conditions of 6-8°C. Egg production is monitored by sonogram and, when ready, the water is gradually heated to spawning levels.

Most sturgeon farms kill the fish to harvest the eggs, but some use something akin to a caesarean section, cutting them open to remove the eggs and then sewing them back up.

Thai Sturgeon Farm’s method is more like milking: the eggs are induced from the oviduct and collected in bowls. This involves lifting the fish out of the water on a form of stretcher. A worker then uses a slender metal rod to help move the eggs.

Some sturgeon live for hundreds of years, producing eggs their entire lives. A single female can produce more than 100,000 eggs at a time.

Despite the challenges of the tropics, there have been unexpected benefits to operating in a warm climate. Fish mature more rapidly in warm weather than in their native chilly north. Much, much more rapidly.

The sturgeon milked in July and November were less than six years old. Tyutin says it would take ten years to reach that level of maturity in China and 12 in Russia. ‘In Novosibirsk, there is snow and ice for five months. The fish don’t grow. They sleep for five months.’

Chefs in Thailand are already keen to start using the product and nobody more so than Thitid Tassanakajohn, or Chef Ton, a rising star of gastronomy in Bangkok. He left a career in finance in New York to return to Thailand, opening Le Du, which just received its second Michelin star and was ranked fourth in Asia’s 50 Best Restaurants list.

Chef Ton uses caviar to spice up some of the Thai-style dishes at his new Lahnyai Nusara restaurant in Bangkok’s Sathorn District, the saltiness supercharging the traditional curries. Ton’s goal is to showcase traditional Thai recipes and flavours in modern forms.

Caviar was common in Old-World palaces, but never made it to the royal kitchens of old Siam. ‘We’re excited,’ Ton says. ‘We’ll definitely be doing more with Thailand caviar.’

This story was published in the January 2022 issue of Geographical, the magazine of the Royal Geographical Association

Source: Inside Thailands first caviar farm.